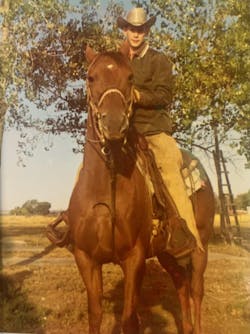

It was not uncommon for boys growing up in the 1960s to dream of becoming cowboys. Spaghetti Westerns were all the rage, and perks of the job included rolling hills, big skies—and bigger steaks—and, most of all, the freedom to make your own way. The lifestyle hooked Jim Mathis when he moved to La Grange, Wyoming, from Michigan in 1969.

“All I wanted to do when I got to Wyoming was become a cowboy,” Mathis recently recalled to Fleet Maintenance.

But life never happens the way you expect. Over the next several decades, Mathis found his true calling was in trucking—more specifically, steering the next generation of automotive, diesel, and collision technicians as president and CEO of WyoTech, a for-profit technical college in Laramie, Wyoming.

And it’s a good thing Mathis did, as the vehicle repair sector has suffered from a drawn-out drought of incoming young talent over the course of many years, while the old bulls have headed out to pasture. This dynamic has created a technician shortage, and educators like Mathis who marshal interest and enrollment in the trade are all that stand between America’s cars, trucks, and heavy equipment getting where they need to go and gathering dust.

Mathis, a former Wyotech student, instructor and executive, has been integral to the school's resurgance in recent years. Founded in 1966, the trade college came under fire afterits previous owner, Corinthian Colleges, was found to be misrepresenting the success of its graduates and sold the school in 2015. Mathis, who was also WyoTech president from 1998-2002, knew there needed to be a new sheriff in these parts, so he rounded up a posse of private investors. With a bit of help from the state representatives of the good state of Wyoming, he was able to obtain the school from the interim owner, Zenith Education Group, in 2018.

What he bought was not the training juggernaut he previously presided over. He started with a dozen students, down from thousands. Since then, the school has gone from a ghost town to a booming mine for skilled techs. According to the school, enrollment has risen 9,000% during Mathis’ tenure. In 2022, the school also completed a 90,000-sq.-ft. expansion, with more on the way.

Read more: WyoTech rises to meet increasing technician demand

“This turnaround has had its challenges,” noted Cindy Barlow, WyoTech’s director of industry outreach. “Just as we were about to take off, COVID hit. Jim proved that it was just a bump in the road and that we needed to put the truck into 4-wheel drive and stay teaching in our shops and classrooms.”

While much of the country locked down and learning went virtual, Barlow said Mathis “was adamant that we stay in the shops and in our classrooms, so we did.”

She added that the humble and tenacious Mathis is the “True Grit” of Wyoming and “has always risen above life’s adversities and came through it all tougher and stronger.”

With WyoTech brought back to life and his mission accomplished, the self-professed “wannabe cowboy” stepped down from day-to-day operations on Nov. 1. A member of Mathis’ staff, Kyle Morris, who has been with WyoTech for 20 years, now assumes the role of president.

Mathis, meanwhile, retains ownership and remains CEO, though he prefers the term “Catalyst.” You could say he is hanging up his spurs, but he’ll actually have them on more often. The ranch owner and avid team roper will be spending more time working with his horses in Arizona, where he has owned a house for the last few years.

“The last couple of winters, I've been freezing to death up here, and at my age, I'm gonna go try to stay warm for the winter,” the 66-year-old said.

He noted the team he put in place handles most of the daily operations business now, and this just makes it official: “It’s not fair to the team for me to be gone and still hold the title.”

But at WyoTech, he will always hold one title: Legend.

From ranches to ratchets

The story of how Jim Mathis turned WyoTech around began in a school, though he had very different feelings on education (at least the standardized kind) at the time. He was 14 and intent on the cowboy life, setting his plan into motion by leaving home to live and work on a farm and ranch.

“I hated high school because it was all theory and no practical [education],” Mathis said. Like two other students in his class of 12, Mathis scheduled his coursework to graduate at the end of his junior year while receiving the practical experience of working with livestock and fixing up equipment on the ranch.

According to Mathis, a month before he was set to get his diploma, the school board raised the credit hour requirements to get more school funding. He decided to leave anyway, quitting school and getting his GED shortly after. Then he signed on with a custom combine crew to harvest wheat in Texas.

It was at that time a new trade wrangled Mathis’ heart: trucking. He started driving semi-trucks during the winter in Nebraska, Oklahoma, Kansas, Wyoming, and Colorado, and his career goals shifted to owning a trucking fleet of his own. With his new goal in mind, Mathis went back to Wyoming in 1976 to enroll at WyoTech. He joined a class of 80 students in the diesel program; the school had 200 students in total.

Read more: Trade school vs. college: Experts, students weigh in

During his time at WyoTech, Mathis’ career goals changed once again, while remaining firmly planted in trucking. He was influenced by “an amazing teacher” named Marlowe Jones to become an educator himself.

"I thought, 'The heck with owning semis; I want to come back and teach,'" Mathis recalled.

So teach he did. Mathis graduated from WyoTech that June and became an instructor there five months later. He rose through the ranks as an assistant training director, then training director of diesel.

This first stint at WyoTech lasted 26 years, “minus the three days when I was fired [in 1990],” Mathis explained.

His temporary unemployment was due to a fastidious executive, while Mathis liked to shoot from the hip. Their philosophical differences led to a showdown that Mathis lost. He still remembers the date and time: “August 20, 1990, at four o'clock in the afternoon,” and he held on to the letter of termination, too.

Almost immediately after his dismissal, the then-president of WyoTech talked Mathis into coming back as a vice president. He spent some time in admissions and marketing, and in 1998 became the college’s president.

In 2002, Corinthian Colleges bought the school for nearly $85 million. Expecting a clash between his maverick personality and corporate culture, Mathis left. He saw this as an opportunity to go from “wannabe” to real-deal cowboy and purchased a cattle ranch, where he worked when not acting as a school turnaround consultant.

Cleaning up the town

The life of a part-time rancher, part-time consultant worked for the next 15 years. Then in 2017, Mathis heard rumblings that WyoTech might be closing down. It had campuses in California, Florida, and Pennsylvania at the time, and a whole heap of trouble due to its new owners.

Corinthian peaked at 110,000 students and 105 campuses in 2010, according to the U.S. Department of Education, but by 2015, the DOE uncovered widespread fraud at WyoTech and Everest, another Corinthian program. Then-California Attorney General Kamala Harris provided evidence in the joint investigation of the college chain that made billions off federal loans.

The lawsuit, filed in 2013 by Harris, alleged that Corinthian used “false advertising and deceptive marketing targeting vulnerable, low-income students and misrepresenting job placement rates to potential and current students, investors, and accrediting agencies.”

"Corinthian preyed on vulnerable students who are now buried under mountains of student debt," Harris said in 2015.

So many students couldn’t find jobs after graduation and defaulted on their loans that the government announced last year that 560,000 borrowers would receive $5.8 billion in full loan discharges.

Undeterred by the school’s now infamous reputation, or maybe driven by it, Mathis’ group was able to borrow enough through state funding to purchase WyoTech in 2018 from the school’s interim owner.

Now as CEO of WyoTech, Mathis, who had helped WyoTech grow for so many years, had to start virtually from scratch. The school had only 12 students, and they were set to graduate after completing WyoTech's nine-month program when Mathis arrived. To retain WyoTech's accreditation, the class of 12 agreed to take an additional elective, extending their studies for 90 days. Afterwards, the team recruited 25 more students to start in October.

There was really nowhere for WyoTech to go but up, though the rate of ascent is something to behold. The campus has taught 2,500 students since Mathis’ ownership, with over 1,000 students currently enrolled, according to Barlow. She was hired by Mathis in 2018 and works with fleets and shops to strengthen the industry's participation with WyoTech, helping to ensure their students have the best opportunities for employment after they graduate.

The school offers many more opportunities for female students as well. Although females represent around 3% of the sector's technicians, WyoTech has had more than twice that number in recent years. In addition, the school has started the Women of WyoTech (WOW) club to assist female students with day-to-day support and career guidance.

Read more: No woman's land no more: Female technician breaks barriers

And because of the technician shortage, no student at the school is wanting for opportunities. Some companies, such as John Deere dealer C&B Operations, will even fly technicians out to their facility. They have offered several students jobs even before they finished the nine-month program.

“The shortage of technicians is not a problem of the future, it is now,” said Adam Somers, regional human resources manager for C&B Operations. “This has a large impact on not just C&B Operations but on many other companies across the nation. It greatly impedes the ability of companies to repair products and return them to customers in a timely manner. Industry partners such as WyoTech have been a blessing, producing quality students to bridge that gap of the supply meeting the demand.”

There will likely be a time soon when the lack of maintenance professionals slows down the U.S. transportation sector, as the commercial vehicle maintenance industry could be facing a shortfall of almost one million techs by 2026. That’s when Mathis’ master plan to mass produce techs may pay dividends.

Along with the 90,000-sq.-ft. expansion, which added eight classrooms and the Dave Kuhn Training Facility shop space, the school acquired an additional site in October, formerly Wyoming Game & Fish, to start a welding and fabrication program in spring 2024. Then to accommodate the growing program size, WyoTech wants to build more housing to suit an additional 3,000 to 3,500 students by 2027.

“Our ultimate goal is to have 10,000 students by 2030,” Mathis said last year.

More importantly, Mathis installed safeguards to ensure WyoTech does not repeat past mistakes trying to increase enrollment. One is verifying students can pay without school scholarships, which Mathis said makes some students subsidize others.

“We know how every single student is going to pay before we ever allow them to start,” said Mathis, who explained this could be through Title IV federal financial aid or the GI Bill for veterans.

WyoTech also now has students sign a professionalism code of conduct, and stay clean shaven and free of rings and visible piercings. Students will also be expelled if they miss three days of class in a six-week period. “[It's] because we are training professionals that have to be accepted by our employers,” Mathis said. “We have two customers to serve: our students and the employee that hires them—and they both have to win.”

Riding into the sunset

Mathis’ new arrangement traveling back and forth between Wyoming and Arizona every few weeks will allow him to have his cake and cow pies, too. He gets to come up with ideas for growth and change and hand them off to his protégé, Morris.

Morris, most recently VP of operations, started at WyoTech in 2003, right after Mathis finished his first stint. He started out as a director of student services and student success.

When Mathis gained control of the school, he gave Morris more responsibility.

"He took a gamble on me and let me run with some of the financial side of the operation and then more and more of the operation over those five years of his ownership," Morris said. "Fortunately, he has granted me the opportunity to take the reins on the whole operation as he takes some more time to himself."

How will Mathis spend that time?

“I’ll probably just drive my team nuts,” Mathis laughed. “I'm a dreamer and a schemer, always thinking outside the box. But our growth plan is going to need a lot of financing, so I'll go out and work with people to figure out how we can finance that.”

When not doing that, the United States Team Roping Championship member will likely be up on a saddle.

In the meantime, the school still won't be without a Mathis on the premises. While the man himself will still be a regular occurrence on campus, his family members, Isabelle and JD, will also continue serving WyoTech as a marketing projects coordinator and program coordinator, respectively. All three will continue to support the school as it, along with every other diesel technical school, corrals incoming technology as electrification and automation enter the trucking sector.

“As long as we continue to stay up with our curriculum and keep [the industry] informed, and they keep us informed of the changes that they need in what we teach, we will change with the times,” Mathis agreed. “When they need multiple technicians in a particular area, such as for hydrogen or electric vehicles, we should be right behind them, changing our curriculum to provide techs for them.”

Morris’ main job now is to build on what Mathis left him.

“We're really poised to continue that momentum and really make sure that our students not only have great opportunities and great careers set in front of them but also respect,” Morris said. “This is not a less-than pathway,” Morris concluded. “This is an equal pathway or a greater-than pathway [to traditional colleges].”