‘Destined to fail’: Trucking leaders, Congress question GHG3 final rule

The trucking industry has been handed a new set of marching orders in the form of the Environmental Protection Agency’s final rule for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards for Heavy-Duty Vehicles-Phase 3 (or GHG3 for short).

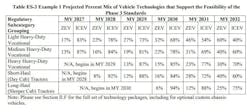

To meet progressively stricter emissions goals to combat climate change, starting in 2027, heavy-duty truck manufacturers will have to make a certain amount of zero-emission vehicles. As of now, that means making more battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) or fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). For example, to satisfy 2032 emissions goals, a quarter of an OEM’s long-haul (sleeper cab) tractors and 40% of its short-haul (day cab) trucks made could not produce any tailpipe emissions. GHG3 begins taking effect with MY 2027 light heavy-duty vocational needing 17% ZEV sales, and medium heavy-duty vocational 13%. By MY2032, these shares would need to be at 60% and 40%, respectively.

These efforts to clean up the transportation industry and improve the environment, while noble, could inevitably lead the trucking industry off a cliff, according to detractors.

These include Republicans in Congress, the American Trucking Associations, the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, and leaders at the fleet level, who have all voiced serious concerns over the current aggressive timeline.

Read more: Analysis: The dark side of electrification

One of those fleet leaders is Taki Darakos, VP of vehicle maintenance and fleet service at Pitt Ohio, as well as chairman of the Technology & Maintenance Council’s S.11 Sustainability & Environmental Technologies Study Group, who addressed the United States House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure Subcommittee on Highways and Transit on April 30.

Pitt Ohio is a less-than-truckload carrier that operates from the Midwest to the East Coast and has 950 company-owned tractors, 2,900 trailers, and 600 straight trucks. The fleet has tested Volvo’s VNR Electric in regional hauls around Cleveland, and the terminal also recently acquired some Freightliner medium-duty batter-electric straight truck, the eM2. The terminal itself has solar panels, and innovative narrow wind turbines and is about as sustainable as you can get in the aging industrial Cleveland suburb of Parma, Ohio.

“Although we continue to be optimistic about the promise of electrification in medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, we continue to encounter challenges related to costs, vehicle range, durability, and charging infrastructure that complicate broader deployment of heavy-duty battery-electric trucks,” Darakos stated.

A major flaw is following the lead of the California Air Resources Board, which effectively will ban the sales of diesel trucks in the state by 2036. That might work in the Golden State, but the nation is a vast place, and federal mandates impact Parma and everywhere else from Juneau, Alaska, to Miami.

“California’s Advanced Clean Trucks (ACT) and Advanced Clean Fleet (ACF) rules are designed to move the commercial vehicle industry as quickly as possible towards zero-emission technology, ignoring the lack of supporting infrastructure,” Darakos explained. “Therefore, these regulations are destined to fail.

“EPA’s decision to grant California’s Clean Air Act waivers to enforce policies that are unworkable for the trucking industry—policies developed via a process that wholly discounted and marginalized trucking industry participation—will result in unworkable regulations and undermine long-term cooperative efforts to reduce emissions,” he continued.

Landscape of confusion

Before discussing the industry's specific concerns about GHG3, we need to explain the regulations' intended purpose.

Some (or a lot) of the opposition has called these new EPA standards “EV mandates,” though the rule is technically technology-neutral. Other avenues to meet the criteria involve advanced internal combustion engines (ICE) fueled by hydrogen, renewable diesel, and CNG, along with hybrids/plug-in hybrids.

“The EPA specifically goes out of its way to say, ‘Hey, these are not mandates for the type of vehicle; it's the mandatory reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, mainly grams per ton mile of CO2,’” explained Dan Moyer, FTR Transportation Intelligence, senior analyst, commercial Vehicles, at FTR Intelligence.

There are many other ways to satisfy the GHG standards, noted Moyer, a former Paccar and TORC Robotics analyst. “When [the EPA is] talking about these compliance pathways, it's not just the engine that's being used or the fuel. It's also additional enhancements and aerodynamics and transmissions, utilizing low rolling resistance tires, and things like that.”

How it will all play out is still an unknown.

“This is a topic of much confusion,” Mike Roeth, executive director of the North American Council for Freight Efficiency wrote to Fleet Maintenance when asked what all this means.

He pointed to the GHG3 executive summary, which offered an alternative non-ZEV pathway to compliance that would comprise: “GHG-reducing technologies for vehicles with ICE ranging from ICE improvements in engine, transmission, drivetrain, aerodynamics, and tire rolling resistance; the use of lower carbon fuels (Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) / Liquified Natural Gas (LNG)); hybrid powertrains (Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEV) and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEV)); and hydrogen-fueled ICE (H2-ICE).”

Roeth, who formerly worked for engine manufacturer Cummins, does not see this method as probable.

“The EPA suggests that the rule can be met without selling BEVs/ZEVs,” Roeth noted. “I think that is highly unlikely as the OEM that would choose to do that would be behind in the overall long-term ZEV adoption.

The NACFE leader has been out in front helping the industry vet zero-emission technology and how it can feasibly fit into the current landscape. He has also educated the general public across the U.S. and politicians on Capitol Hill. In April, he moderated a webinar for the EPA to help explain the subject.

Roeth, who has been a staunch advocate for efficiency add-ons such as aerodynamic kits and low-rolling resistance tires, along with near-zero emission CNG powertrains, stressed that fleet comments were taken into account when devising the final rule. He told Fleet Maintenace the EPA “increased the credit opportunities” and “delayed the implementation for all segments.”

In a May 1 statement criticizing the final rule, the ATA noted the rollback, but argued that will on;y limit fleet choices in the future: "While EPA’s final rule includes lower zero-emission vehicle rates for model years 2027-2029, forced zero-emission vehicle penetration rates in the later years will drive only battery-electric and hydrogen investment, constraining fleets' choices with early-stage technology that is still unproven. The trucking industry needs technology-neutral policies that allow for innovation and alternative fuel sources like renewable diesel, which generates a lower lifecycle carbon footprint than battery-electric vehicles at a fraction of the cost."

Republicans weigh in

In response to the GHG3 final rule, some Republican senators and House representatives have struck back with Congressional Review Act legislation to block the GHG3 rule for heavy-duty, as well as similar EPA rules for light and medium-duty vehicles. Through the CRA, members of Congress can overturn agency final rules, a method successful 20 times (out of around 200) since its inception in 1996.

Both pieces of legislation were introduced by Republicans—Sen. Pete Ricketts (R-NE) and Rep. John James (R-MI-10) for the LD/MD rule; Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-AK) and Rep. Russ Fulcher (R-ID-01) for the HD one. The HD bill has garnered co-sponsorship from 46 Republican senators and the LD/MD one from 40. Though billed as bipartisan, the only Democrat to sign his John Hancock was Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV).

Rep. Fulcher asserted many areas across the U.S. will difficult to deploy ZEVs.

“Rural communities around Idaho are not able to implement the massive grid expansion that would be needed to support the electrification of heavy-duty trucks,” Rep. Fulcher stated. “These vehicles consume roughly seven times as much electricity on a single charge as a typical home does in a day and charging centers can require as much power from the electrical grid as a small city. Infrastructure aside, electric trucks cost roughly twice as much as diesel trucks, and these vehicles are not able to haul nearly as much.”

“President Biden’s EV mandate is delusional,” stated Sen. Pete Ricketts (R-NE), who along with Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-AK), introduced the LD/MD legislation. He also alleged the move would make the U.S. more reliant on China, a leader in electrification.”

Sen. Sullivan called the EPA rules “ludicrous,” and noted federal mandates for EVs simply would not work reliably for his Alaskan constitutes due to cold temperatures’ impact on batteries, as well as how far cities are from each other.

“Make no mistake, this thinly-disguised attempt to get rid of the internal-combustion engine without congressional authority will only hurt hard-working families across the country, worsen the supply chain crisis, and deepen our reliance on Chinese Communist Party-controlled critical minerals,” Sullivan also stated.

Greenhouse to poorhouse?

In a statement, the EPA lauded the long-term impact of this final rule, estimating the new “standards will avoid 1 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions [by 2055] and provide $13 billion in annualized net benefits to society related to public health, the climate, and savings for truck owners and operators.”

Particularly for the heavy-duty industry, the EPA projects the new standards will save $3.5 billion annually from 2027 to 2055 while accruing $1.1 billion annualized costs of about. That equates to $98 billion saved and $30.8 billion spent.

“A purchaser of a heavy-duty truck in 2032—when the standards are fully phased in—could save between $3,700 and $10,500 on fuel and maintenance costs annually, depending on vehicle type,” the release stated.

"We are concerned that the final rule will end up being the most challenging, costly, and potentially disruptive heavy-duty emissions rule in history," responded Jed Mandel, president of the Truck and Engine Manufacturers Association.

Before the final GHG rule was announced, a study by consulting firm Roland Berger commissioned by Clean Freight Coalition estimated the costs to fleets to electrify all medium- and heavy-duty trucks would be nearly $1 trillion. This is due to largely to charging infrastructure, accounting for $620 billion. Another $370 billion would need to be invested by utilities to upgrade grid networks. The average charging infrastructure cost could be $145,000 for each HD truck and $54,000 for each MD one, the study alleged.

“The EPA has historically overlooked the impacts these regulations have on small businesses,” offered Todd Spencer, President of OOIDA. “This has led to a wide variety of problems for the trucking industry, especially when manufacturers are forced to meet unachievable implementation timelines. This results in more downtime and higher maintenance costs because the newer vehicles end up being less reliable when they first come out.”

Sustainability also comes at a great cost to the fleets and taxpayers.

“Before incentives, a Class 7/8 battery electric truck can cost two to three-and-a-half times more than its comparable diesel model, and a hydrogen fuel cell Class 8 truck can be as much as seven times more,” Darakos noted. “In our fleet, we have found acquisition costs to be roughly three-fifths of the total cost of operation. For many fleets like ours, that calculation is often complex and cannot be done without significant trial and error and at great capital expense.”