Long-haul trucking's zero-emissions future fueled by hydrogen, NACFE report says

Although using hydrogen fuel cells in freight transportation is still in its infancy, they are currently the only viable zero-emission solution proposed for long-haul trucks, according to the latest guidance report from the North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE) and RMI, which updates a 2020 report.

The report, Hydrogen Trucks: Long Haul’s Future?, focuses on using hydrogen-based powertrains for Class 8 long-haul freight routes pulling van trailers. These powertrains include a range of fuel cell battery-electric types and hydrogen internal combustion engines based on the diesel cycle.

“As we move to the zero-emissions freight future, in the long run, there are only two choices of power—battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell,” said Rick Mihelic, report author and director of emerging technologies, NACFE.

While purely electric trucks have already accrued years of service on regional routes, their batteries' capacity and sparse amount of charging stations limit how far from home they can go.

“As much as we appreciate battery-electric vehicles, they aren’t set up to go those really long distances with heavy loads,” Mihelic added during an April 4 NACFE press conference. “So, right now, the only thing that’s on the plate for a zero-emission future in long haul will be hydrogen-powered vehicles.

Read more: The dawn of hydrogen trucks

The latest guidance report is based on two previous NACFE reports—Viable Class 7/8 Electric, Hybrid and Alternative Fuel Tractors and Making Sense of Heavy-Duty Hydrogen Fuel Cell Tractors—which compared a range of alternative fuel heavy-duty truck technologies, including hydrogen.

This latest report looks at what NACFE got right the first time around, as well as what the team missed.

The accurate forecasts NACFE hit on include:

- Hydrogen fuel cell adoption is being driven by regional and national regulations rather than trucking.

- BEVs are the baseline for hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles (HFCEVs), as opposed to internal combustion engines.

- Fleets should optimize the specs of their HFCEVs for what they need them to do, and expect trade cycles to increase

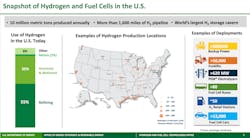

- The proliferation of HFCEVs rests on the production and distribution of the hydrogen fuel, not the vehicles or fueling stations.

- The onset of autonomous trucks will help the case for HFCEVs to run 24 hours a day.

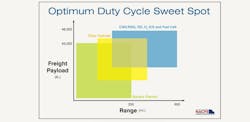

“The story around hydrogen is that it is not the solution to every duty cycle, but it is a solution to part of the spectrum that diesel engines are doing today,” Mihelic said. “In this future that we are going to, there are different solutions for different duty cycles. Primarily, hydrogen fuel cells are going to be used for the heavy-duty longer-range vehicles.”

When it comes to hydrogen, one thing that comes up all the time is the colors of hydrogen, which indicate how sustainably the hydrogen is produced. In writing the latest report, Mihelic said the industry has begun talking about carbon intensity rather than the color, but NACFE says both are relevant.

“With carbon intensity, you don’t really care how [the hydrogen] is produced as long as the carbon intensity is properly managed,” Mihelic explained.

In its latest report, NACFE also discusses how the creation, distribution, and storage of hydrogen will weigh heavily on its net commercial cost. As Mihelic pointed out, it's also important to note that hydrogen can’t be “built solely on the shoulders of long-haul trucking. There just is not enough demand to increase the production needs on trucking alone,” he said.

According to the report, hydrogen costs will decrease as the scale of the hydrogen plants increase, and large production requires multiple industries to increase demand for hydrogen. For instance, if the steel and cement manufacturing industries migrated to hydrogen, transportation could tap in.

“But trying to force steel into hydrogen because the transportation network has gone to hydrogen—there just isn’t enough demand for the vehicles to push the volume sufficiently,” Mihelic emphasized. “It really has to be the other way around.”

Hydrogen ICE vs. fuel cells

One thing NACFE missed in its first report was the implementation of hydrogen in internal combustion engines—even though certain duty cycles, like off-road vocational and emergency vehicle applications, could be a good fit for hydrogen ICE.

Cummins' X15 hydrogen engines, which will go into production in the latter half of the decade, have received plenty of fleet attention already.

“There are a lot of things appealing about a hydrogen engine because it primarily looks like what you buy in a diesel engine today,” Mihelic noted. “It still suffers that infrastructure issue in that you need to get the hydrogen out there, but it may be less of a leap of imagination for fleets to move to a hydrogen engine before they move into fuel cells.”

The question really becomes whether hydrogen ICE from an efficiency standpoint will match what fuel cells can do in terms of the consumption of the hydrogen, Kevin Otto, NACFE’s electrification technical lead, explained. Either way, Otto said the distribution of hydrogen has the same challenges regardless of fuel cell or internal combustion engine.

“We’ve been looking at scenarios and how many technologies different fleets will go through,” said Mike Roeth, NACFE's executive director. “One thing to think about is you could transition to hydrogen engine on your way to hydrogen fuel cell, but that’s another step change and another step of education, capex, and changing your operations. How much of that can you handle?”

Hydrogen, electricity, working through the unknown

In its report, NACFE also indicates that hydrogen fuel cells will be a factor in future long-distance freight hauling in combination with battery-electric vehicles for shorter range operations. It's also worth noting that hydrogen is closely tied to electricity.

“The other thing to think about is hydrogen is inherently resilient,” Mihelic said, comparing hydrogen to the volatile oil market. “Hydrogen and electricity are both produced through multiple mechanisms and that inherently stabilizes the marketplace.”

“Think of hydrogen as a ‘gaseous battery.’ The key factor in going hydrogen fuel cell is a fleet’s need for availability of the vehicle for multi-shift, multi-route operations,” said Mike Russell, senior project lead – zero emissions powertrain, Paccar Inc.

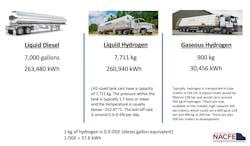

Roeth noted that although the industry doesn’t need to know everything to get started with hydrogen fuel cells, there are key unknowns that need to be determined before trucking can move fast. One of which, he said, is gaseous versus liquid hydrogen, both on the truck and in the distribution of the hydrogen from point of origin to the truck stop or depot.

Gaseous hydrogen, for instance, must be shipped on many more trucks and trailers compared to liquified hydrogen, which can be shipped like diesel—via one tanker.

“When you do look at truly zero-emission freight there are two solutions—battery-electric and hydrogen fuel cell,” Roeth said. “And it’s not going to be an either/or, it’s going to be an and. The question becomes how much of each?”

“We know battery electric is here and will come ahead of fuel cells,” Roeth added. “And we’re going to learn a lot, even in the short range, lower payload areas where we believe the battery-electric truck gets vastly better over the next years.”

The reality today is that battery-electric trucks and their infrastructure have a head start on hydrogen fuel cells.

“All the answers don’t need to be known on day one of hydrogen,” Mihelic said. “There’s a lot of pressure to know all the solutions and jump to the end of the book on day one, but this is a journey that we are going to be taking for a while.”

This article was originally published on FleetOwner.com.