ORLANDO, Florida – At this year’s American Trucking Association Technology & Maintenance Council Meeting, much of the focus was directed toward developing vehicles of the future, especially as many fleets have already taken steps to decarbonize their operations. The event’s first technical session of the conference, entitled ‘Powertrains of the Future!’ addressed the many options fleets have at their disposal while discussing some of the challenges and considerations they must make during the process.

“There is no silver bullet,” said Ken Marko, senior national fleet sustainability engineer, U.S. Foods. “We have a lot of applications in this industry to consider.”

The session’s panelists included a range of professionals from several aspects of the industry, including suppliers, fleets, manufacturers, and the North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE). Among them were Dr. Ameya Joshi, director of emerging technologies, regulations, and electrification, Corning Inc.; Adam Buttgenbach, director of fleet engineering and sustainability, PepsiCo; Mark Ulrich, director of customer support, Cummins; Robert Reich, executive vice president, chief administrative officer, Schneider; and Michael Roeth, executive director, NACFE.

Read more: New, pending, and possible rules and regulations facing fleets in 2023

State of the powertrain

To begin the session, Dr. Joshi gave an overview of the industry's diesel efficiency and sustainability progress, especially in light of the drastic reduction in NOx and particulate matter (PM) regulations over the past 10 years.

“Nine hundred trucks today [make] the same amount of NOx and PM as one truck in the 1990s,” Dr. Joshi emphasized. “Think about that. That’s how clean trucks really are.”

However, Dr. Joshi noted that even with these gains, the industry still has marked room to improve, especially if it is to meet the new EPA regulations for model year 2027 trucks.

To meet these future challenges, the industry has several options for the future of powering its fleets, which range from battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) to hydrogen-powered vehicles. But neither of these options are without their drawbacks.

“We already have a lot of [EV] trucks that are out there in the 100 to 250-mile range. Long haul, not so much,” Joshi explained. “If you want to do a 500-mile plus drive every day, you need a one-megawatt-hour battery. One megawatt hour, to put it in context, is the power an average US home would use for an entire month."

Meanwhile, while the range of electric vehicles can be prohibitive, hydrogen-based vehicles face a similar pitfall.

“Roughly, [hydrogen] trucks use about 15 kilograms of hydrogen for every 100 miles,” Dr. Joshi reasoned. “Now, if you do the math for that, to convert a quarter of all of the Class 8 sectors in the U.S., you’d need about 9 million tons of hydrogen. That's about the overall hydrogen that's used by the entire U.S. economy today. So, you're talking about doubling the hydrogen production, getting it from green sources, and using it to power only a quarter of the Class 8 fleet.”

While Dr. Joshi reported that these staggering numbers are not impossible, it does require significant development in infrastructure to produce green hydrogen and lower costs overall. For electric vehicles, too, moving forward necessitates massive infrastructure support, for which public investiture is vital.

“Ultimately, none of this really matters unless we can drive wide-scale customer adoption of [green fuel sources] in the market, which means we have to continue to be very focused on the highest reliability standards, durability standards, and fuel efficiency standards that our customers demand to serve the markets that they operate in,” Ulrich commented.

So, despite the hurdles inherent in their structure, several companies have moved forward in developing alternative powertrains, whether they are electric or use alternative fuels.

Electric vehicle development

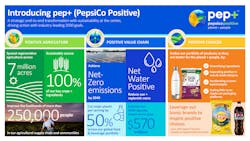

Of the many options available to fleets and manufacturers, electric vehicles are a stand-out choice for fleets with drastic emission-reduction goals, such as PepsiCo, whose pep+ (pep Positive) initiative focuses on sustainability for the company in three aspects: Positive Agriculture, Positive Value Chain, and Positive Choices.

“For this audience, I want to touch on that center pillar, where our private fleet operates and has an impact on what we do,” Buttgenbach said. “And that's the net zero emissions by 2040 that we're working on.”

But meeting these goals via electric vehicles has necessitated careful calculation for PepsiCo, including tailoring their electric vehicle usage to the duty cycles most applicable for them.

“Where we've deployed our battery electric vehicles, some of the considerations that we've made on our pilots as well as our large-scale launches is what is the duty cycle of that equipment? Will it be in a 24/7 operation where we need to have a megawatt-level of fast charging or is it in a situation where we can slow charge the vehicles overnight?” Buttgenbach asked.

Additionally, PepsiCo considered what percentage of the company's assets from any one distribution center was electric, with the possibility of scaling up their investment over time. Critically, for both charging and electric-vehicle ratios, Buttgenbach emphasized that deploying these new technologies couldn’t disrupt business operations, as the negative feedback generated by doing so could hinder future adoption.

“We also want to understand the size of the project,” Buttgenbah continued. “How many miles are we renewing that could influence the amount of power we need from the grid, [what’s] the full scope of the utility project? When we start a project, and we go in and we have to dig up a parking lot to put in an ESC, are we able to lay all of our conduits at one time, and only put in the charter for the initial launch and then come back in and scale as the business scales appropriately?”

Schneider found the hurdles of tackling the power grid infrastructure a difficult one for their electric endeavors as well, as the company is in the process of deploying around 90 Class 8 battery electric vehicles in Southern California.

“The price of electricity swings dramatically throughout the day,” Reich explained. “So, we need to have a plan of charging these trucks and make sure we're not doing it at peak charging hours. But really, where all our lessons are, and the big changes, is on the infrastructure side. And not only working on the on-site infrastructure but working with the power company to make sure everything's in place.”

Schneider is putting in four power cabinets, each rated at 1.2 megawatts so that the solution provides roughly 4.8 megawatts in total. Each power cabinet has four charging posts, 250 kilowatts each, and each with two charging cables so that the full solution could charge 32 vehicles at a time, although Reich stated that the company is likely to start with 16 vehicles to utilize a 2-4 hour charging cycle.

However, Schneider’s plans with Southern California Edison (SCE Corp), the primary electricity supply company for much of the region, have been delayed due to chages in thne local grid. Initially, the company agreed that it could handle sending 4.8 megawatts to the transportation company.

“Fast forward two years later, we get the grant money, we're ready to go,” Reich said. “And guess what happened in El Monte California? There's a whole bunch of new buildings that weren't there two years prior when we first [approached the SCE]. So, the response from the SCE was ‘We can’t do 4.8. right now, we're gonna have to do a lot of development to get you guys squared away.’”

The complexities of establishing the electric infrastructure also delayed Schneider’s deployment plan, too.

“When we brought on the first initial test truck, we were bringing on a very simple charger to support that one truck,” Reich recalled. “[It] wouldn't work with the power company, their local transformer wouldn't support this very small, basic charge that we put on site. It caused a three-month delay in the project while they brought in a new transformer to support a very small charger that we were starting with.”

Part of this project is allocated towards the Joint Electric Truck Scaling Initiative (JETSI), which will deploy 100 battery-electric trucks between Schneider and NFI and 50 truck chargers. The initiative also provides a window into what it takes to finance such a large-scale EV project.

"It's about a $27 million dollar budget to deploy those 50 [chargers],” Reich explained. “Schneider's proportion of that is about $9 million.”

Of this $27 million, $19 million is funding the 50 vehicles. About $2.1 million went towards on-site charging equipment and construction costs, although the project has reportedly gone over this number. Another $2.5 million went towards SCE, and the endeavor currently assumes it’ll cost about $2.7 million for the electricity to power the trucks for two years.

Of course, none of this covers the money to ensure proper training and tools on the maintenance side, which is also critical.

“Buy-in from the field operations team, making sure we have good communication with our technicians, [getting] the proper training on these new vehicles, especially with battery electrics and higher voltage assets, how to safely work on them, how to properly de-energize the technology,” all must be accounted for in terms of rolling out an EV program, Buttgenbach noted.

Alternative fuel developments

With the many considerations fleets have encountered in developing EVs, it makes just as much sense that equal investment has gone toward alternative fuels as well.

“We look at things like carbon intensity certifications depending on different energy sources,” Buttgenbach explained. “When we look at the vehicles and the asset profiles that we have, we've looked at what is the availability of that energy? Is it widely available? Or are these renewable fuels less than 1% of what's actually available on the market? What is the cost of that? What do the economics look like? How competitive would it be when compared to other alternatives? What is the infrastructure in place?”

Sometimes this means looking to diesel efficiency while renewable fuels continue to become more market-effective, especially with the current exigency for cutting emissions.

“To hit our sustainability targets, we have to lower emissions today,” Ulrich stated. "So, what does that mean for customers in the trucking industry? One way we can do that, and we work actively at this, is how we can help customers spec the most fuel-efficient vehicle at the outset.”

One aspect of this is Cummins' X10 fuel-agnostic engine, which was on display in the exhibitor hall.

“A year ago, we announced our fuel-agnostic engine platforms,” Ulrich noted. “We have a new natural gas platform that we're developing for heavy-duty trucks. We have advanced diesel engines that we're continuing to invest in. And then, we also have hydrogen internal combustion engines that we're looking very hard at and how that, with the right green hydrogen, could produce an engine with very low NOx and zero CO2 emissions.”

Hydrogen engines in particular provide an appealing alternative to compensate for the still-developing abilities of EVs despite their cost as a fuel source.

“There's a lot of infrastructure challenges with hydrogen,” Reich admitted. “We know the cost of hydrogen has to come down to be competitive, however, the range is likely going to be longer than your battery electric, so it might fit in as a nice midpoint for a fleet. And if we do continue to have extreme weather options, perhaps hydrogen is a solution in colder climates where battery electric ranges would be limited.”

Powertrain decision-making for fleets

While the sheer amount of powertrain options for fleets may seem daunting, Roeth emphasized that fleets don’t have to face the overload of information alone. Previously, NACFE coined a term for this period in alternative fuel development as the ‘messy middle.’ As the industry has ventured further into this gray area of development, NACFE has clarified and added to its previous definition of the period and the options it presents.

“We've created a new graphic for what we describe as the messy middle,” Roeth explained. “And we believe it's time for action as we look forward. [The current graphic is] similar to what we had before. But we've added a few things we weren't looking at, or didn't think about at the time, such as burning hydrogen in a diesel or an internal combustion engine.”

In response to these developments, NACFE also unveiled a new decision-making flowchart to evaluate various powertrain options via several categories.

“We’re suggesting the industry thinks about this in a couple of buckets,” Roeth said. “Understand the duty cycles, understand your fleet, how you do you operate, where do you operate. Just get a good baseline of what you're doing with your fleet. And then consider these zero-emission, battery-electric vehicles, and hydrogen-fuel-cell electric vehicles that are available for you. Start with those, because that's going to be the end game.”

After this, NACFE advises fleets to consider each fuel source, where it comes from, and how sustainable it is. Finally, fleets need to consider the technology available to them. All of these methods can point toward which solutions are most viable for a particular fleet.

Manufacturers can assist fleets with this process as well, which Roeth advised they do.

“If you're a manufacturer out there, it is very easy to go ‘sell, sell, sell your product' wherever you can,’” Roeth said. “I don't think this is a time for that."

Instead, Roeth advised that manufacturers should help their customers choose solutions that are right for them and not the first solution a fleet may approach them with. This collaboration between each member of the industry is critical to solving the powertrain problems the industry faces today, Roeth emphasized.

“This is a big challenge,” Roeth concluded. “We need to work together, find the right partners, and go make it happen.”