Raj Basran, president and owner of Fleet Fast, never intended to follow in the family business, running a small auto and truck body shop in Akron, Ohio, but life is unpredictable that way.

Basran knows that better than most, as the shop’s success is driven by unpredictable events, like a reckless deer bounding in front of a van’s grille, or a truck driver misjudging a bridge clearance, or those times the side of a building comes out of nowhere to hit the back of a box truck. If life wasn’t messy, Fleet Fast’s parking lot wouldn’t be full of battered box trucks and dented delivery vans.

And just as successful fleets will use these events as teachable moments that help those involved grow and mature, Basran and Fleet Fast have found flexibility in handling the unexpected—whether that’s flipping the customer base, handling planned expansions and an unplanned pandemic, or procuring hard-to-find parts and retaining in-demand technicians—leads to long-term growth.

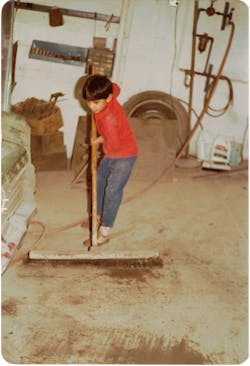

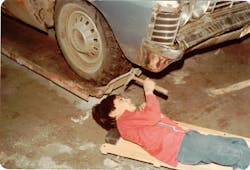

Basran, 51, certainly knew about the business from a young age, as he quite literally grew up where Fleet Fast stands. His childhood home was right next to the corner collision shop, which his father, Ravinder, started up in the ’70s shortly after emigrating from Punjab, India, with his wife, Mukhtar.

“He started the business with very little experience, but a lot of drive,” Basran said of his father, who had previously done some welding in the nearby city of Kent.

Back then, the shop only fixed up cars. Their customers were locals, with likely plenty of Goodyear employees mixed in, as the tire maker’s headquarters is a little over a mile away.

Things changed in the ’80s when the shop landed an account with Wonder Bread, which had a bakery nearby. The house was demolished to make way for three more bays to do commercial vehicle work, and business was good, even as the Rubber City was turning into another Rust Belt casualty.

His parents—worried about their retirement plans—asked their son one question: “Can you make a go of this?’’

“This business that my mom and dad had built up for their entire lives was hanging in the balance,” Basran said. “How do you refuse?”

There wasn’t much deliberation before he accepted the offer.

Cut to the present, and Basran’s office is about 10 yards from where his nursery room was. But while his geographical location has not changed much since the start of his life, the business is in a far better place than when he took over. The first-generation entrepreneur inherited his father’s drive and has transformed the modest body shop into an oasis for broken trucks and vans, and as the boss, he’s found that by treating vendors, partners, and employees like family, that success will continue.

Going commercial

“I wasn’t getting the volume, and after a few years, I realized nobody even wanted to come here for an estimate, let alone drop their cars off,” the former psychology major said. “It’s not nearly as bad as the perception, but that perception is real—and that perception is what I was fighting.”

Ten years ago, Basran decided to stop fighting for customers who would never come and face reality: the shop would have to adapt or all hope for growth, and the ability to provide security for his family, would be lost.

“Failure was not an option,” Basran asserted.

This meant going all in and catering solely to commercial customers.

“Fleets don’t care where your physical location is,” Raj noted.

Fleet Fast offers a complimentary concierge service where shop drivers retrieve the vehicle for repairs and then drop them back off when complete. Now the only perception that matters is if the truck looks like new and was repaired promptly. And what Basran expects from his team on every job—“quality work with a sense of urgency”—is exactly what fleets would expect to become a repeat customer.

It wasn’t easy and everything had to be executed perfectly at the small shop, which had three unusable auto bays and three for trucks.

“In the early days, we were extremely conscious of the workflow; we did not have the luxury of keeping trucks in bays while waiting for parts,” Basran said. “We were fanatical about choosing the right jobs to pull in at the right time. We also would ask for overnight delivery of all parts back then. I would pay the extra charge out of our pocket. This made a huge impact on lowering cycle times.”

And by sticking with the core tenets of speed and efficiency, the business turned around. With the growth of the last-mile segment and drivers’ propensity to hit things they shouldn’t, the business started to see real growth in 2016. Basran bought the lot on the northwest corner of the block and added a building for high-roof vans, and then in 2019, he built a 6,000-sq.-ft. building to rebuild box trucks.

“Low bridges and low branches built this building,” Basran quipped during a tour of the site.

The more serious reason is that companies such as Amazon and Penske want trucks that bear their name to look professional and not like they moonlight at demolition derbies. And it’s very difficult to get new trucks, due to backlogs driven up by chip shortages and COVID-related plant shutdowns.

“We’re seeing a bigger volume from the customers who actually take a lot of pride in their fleets because it’s a lot harder to find new trucks right now,” noted Fleet Fast office manager Ben Cole. “Trucks that have been hit—that normally would have been totaled out—or older trucks they would be retiring, they’re fixing instead. And they’re still making them look top notch for their drivers.”

At any one time, up to 70 commercial vehicles could be in the bays, queued up in one of the shop’s secure parking lots, or in the overflow lot across the street. And Basran noted business revenue has grown eight-fold over when the shop worked on both passenger and commercial vehicles.

“Pre-pandemic, we were probably looking at around 40 to 50 trucks that are works in progress or pulling in at any given time,” Basran said. “Now we’re renting more space just to park them, so that’s an added cost of doing business.”

Basran admitted he was naïve about expansion: “I didn’t realize with every step, we’re going to need more parking.”

Parts are also a major challenge. Extruded aluminum and corner caps for the bodies, as well as certain hoods and other pieces, have pushed back certain repairs by weeks to months. COVID-related shocks to the global supply chain resonate even deeper for smaller shops with little bargaining power, but Basran said larger fleet customers, such as Penske, can help move things along faster.

And while overflow parking has become a struggle, the unused automotive bays allow for ample parts and paint storage.

“A big advantage to our business versus some others is that we hold around $100,000 in parts onsite,” operations coordinator Brian Joseph relayed. “A lot of that is box parts that we can then put on the truck and have a turnaround time much lower than other shops in the area.”

Finding the right tools and partners

The shop has nine technicians, two office employees who handle logistics and estimates, and a few drivers to pick up and drop off the vehicles to fleets. The shop’s technicians constantly buzz around, sanding panels, wrapping a whole chassis in plastic, and replacing corner caps. The team can rebuild an entire straight truck’s box in a week or two. It’s clear from walking around the premises that this small team has fabricated an efficient workflow. However, twenty years ago, the blueprints were fuzzy outlines in Basran’s mind.

“Not having the background of being a tech, or even training in the industry, I knew that I needed to partner up with somebody who could teach me,” Basran said.

After looking around and reasoning a paint company would provide the best support, Basran settled on PPG Refinish, which had recently launched its MVP Business Solutions program. This offering comprises training, consulting, tool help, and more. The MVP operations manual would become Basran’s “bible.”

“When I first started, this gave me all of the key insights into running the facility,” he recalled.

He also connected with a vendor called Autobody Products Inc. (API) out of Butler, Pennsylvania, which provides PPG paints and coatings, tools, and training and service. They remain Fleet Fast’s primary vendor.

Other partners include Morgan Corp., Wabash, Mickey Truck Bodies, Maxon, Waltco, and 3M. Certification partners include I-CAR and ASE.

Having established partnerships and getting the right shop equipment made the transition smoother, Basran said. This included riveters and plasma cutters, DuraPlate application/installation kits, and even truck diagnostic tools.

Basran credits the purchase of eight scissor lifts as making the biggest impact on technician productivity and comfort. The shop previously used stationary and rolling ladders.

“We invested in the best equipment available to ensure that we could be as efficient and fast as possible,” Basran explained. “Down equipment means longer downtime for repairs, so we have strong relationships with our tool vendors in servicing and maintaining. They also provide loaners when necessary.”

Implementing PPG’s AdjustRite automatic estimating software eight years ago also has allowed Fleet Fast to get work orders created and approved.

“AdjustRite is such a robust estimating system that we don’t have to do anything,” said Basran.

The system, accessed from a computer or smart device’s web browser, takes the user step by step and provides populated lists of options to click on. The program draws from a vast cloud-based database, taking into account the truck model, parts pricing, labor, and even smaller costs such as hazmat disposal, to instantly provide an accurate estimate to the customer so work can get started.

“If an estimating system does not have a logic-based function, it’s possible to overlook a certain percentage of costs attributed to parts and/or labor,” noted Doug Orr, manager for AdjustRite. “Even if this number is just 5%, a job estimated at $20,000 could be missing up to $1,000 in costs for these items.”

Before using AdjustRite, Basran said he was writing in everything manually and using automotive estimating templates for the commercial trucks, which proved difficult. That was anything but fast.

“The big thing is speed for us—it’s in the name,” Basran said. And at Fleet Fast, the estimating system also proved to be highly accurate.

Office manager Cole, who performs about 1,000 estimates a year, said the estimates match final cost over 95% of the time. While the estimator can walk around the truck and fill in the fields at the vehicle, Cole prefers to jot information down on a pad using a shorthand he devised. He then plugs the numbers in at his desk, because he also has to man the phones in the office.

Growing up and out

It’s a small crew, so everyone has many jobs. Basran is especially proud of Francisco “Frank” Esquivel, his master technician and right-hand man. Esquivel was an entry-level worker 12 years ago and is now entrusted with the most difficult jobs, such as fixing Freightliner front ends. He benefited from learning from an older technician, Alan Grace, who had worked for truck body manufacturer Supreme Industries, which merged with Wabash in 2017.

Having someone with OE experience who was willing to train others allowed the shop to now expand from basic bodywork to rebuilding boxes, which Basran credited as the major driver of the shop’s current success.

Loyalty obviously matters to Basran, as this shop is more than just a business; it’s his family’s legacy. And because Esquivel has taken advantage of every training opportunity to expand his skillset, Basran has entrusted him with a larger managerial role, including employee hiring and day-to-day performance.

Esquivel had a big role in rooting out the “bad apples,” what he called technicians who would hide in a corner and play on their phones instead of working. But the shop manager realized even when techs are hard to come by, the wrong hires can create more of a workload.

“We threw bodies at the problem just to help us out—and we ended up babysitting,” Esquivel said.

The culture issues stopped around the time the pandemic started, with a new strategy emerging.

“Our philosophy is bringing in entry-level guys with little or no experience and training,” Basran said. “We want to hire people who have a good work ethic, are kind, open-minded, and reliable; everything else we feel like we can train.”

That method had already paid off with Esquivel and his brother, Cristian Fonseca, who started as an apprentice nine years ago. Fonseca received his welding certificate about five years ago and is now a master tech in fabricating and welding.

“The welding teachers come to me and say, ‘Okay, this guy can now teach the course because he’s that good,’” Basran proclaimed. “[Fonseca] basically had mostly on-the-job training, and he learned from the box guys who used to work here full time.”

Basran reasoned anyone who Fonseca trains will gain at least some of the institutional knowledge from those technicians who haven’t worked there in several years. He has already taught another fellow technician, Ty Hayward, a former plant worker at Waltco Liftgates.

“He taught me a little bit about it; I feel comfortable doing it, though I wouldn’t say I’m really good at it,” Hayward offered. Basran took exception to that assessment, saying Hayward is perfectly capable of many tasks.

The Fleet Fast employee of three years does plan to continue training and get even better at welding, which will certainly help the shop. Those skills are always needed to precisely repair door frames and ramp components after being severely damaged. Basran also takes great pride in returning trucks back to OEM standards, even when they come into the shop looking like they went a few rounds with Optimus Prime.

Fleet Fast takes a “homeschooling” approach to its continuous education in all areas, often inviting vendors and OE experts to hold hands-on clinics onsite. Van experts may come in to show where to apply adhesives on side paneling, while an I-CAR trainer may go through welding procedures. This show-don’t-tell method is crucial, as going off written instructions alone can become burdensome. Ford’s procedure for replacing roof panels is around 30 pages, Basran noted.

“Training is a problem in the commercial body shop industry—there’s a big void,” Basran said. “There’s I-CAR and ASE, but we have struggled as an industry.”

One thing Fleet Fast does not struggle with is retention. This starts with all that training and is fortified by competitive wages. Due to the pandemic and now rampant inflation, Basran said he handed out cash bonuses and “brought up our hourly wages accordingly and aggressively with the team.”

It’s also about recognizing who his employees are at heart and allowing them ample time and resources to fix up and modify their personal vehicles. They pay the wholesale cost for supplies like paint.

“If you look at their cars, they build them, they don’t buy them—it’s the old hot rod mentality,” Basran said. “Back in the ’60s and ’70s, everybody would go in their garage and get dirty. You don’t see that anymore. But with our culture, we emphasize that. It’s who we are.”

To attract more of those gearheads to Fleet Fast, Basran has his techs do some soft recruiting of friends with similar interests and at car shows.

“These guys are so resourceful by nature, and they like working on things and with tools,” Basran explained. “So I told them, ‘When you go to the car shows, recruit. When you talk to any like-minded friends, recruit.’ And actually, we got a lot of these guys working here now from the network of people that my guys knew.”

Esquivel recently found three new technicians through his social media network. And while Basran admitted the shop could use more technicians to grow even more, it won’t come at the cost of ruining the family dynamic.

“I’m not going to disrupt my culture just to add more bodies,” Basran concluded. “I feel like we’re better off now post-COVID, strengthening the guys we have now, empowering the guys we have now, and continuing to train them up.”

Even though Basran still works where he learned to walk, he appears miles ahead of where he started.