Speed of electric truck adoption rests on election results

Electric trucks will proliferate fleets at some point in the next decade, but the 47th president will ultimately determine if this is done at a break-neck pace that will disrupt the industry—as many believe the current course will—to turn the tide against the existential threat of climate change, or at a manageable rate that allows everyone to move forward together.

It’s a classic progressive vs. conservative dilemma with freedom vs. security implications. Should the industry lose its freedom to determine what powertrains win and which lose because various scientific data models say if they don’t, hurricanes and droughts will get more severe?

A study by the World Economic Forum predicts climate change could kill 14.5 million people by 2050. The globalist organization also advocates bugs as a “credible and efficient alternative protein source,” so maybe they don’t have our best interests in mind?

Regardless of why electric trucks are being pushed, their proliferation will likely define everything from how much you pay for groceries to how fast freight can be moved. (And in areas with spotty grid reliability, if you can run your air conditioner or run your blender to make a nutritious grasshopper smoothie.)

And there’s no going back.

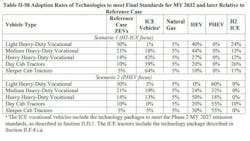

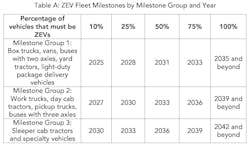

Federal and state regulations are already in place driving OEMs to make and fleets to operate these and other alt-fuel commercial vehicles. The major ones include the Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Standards for Heavy-Duty Vehicles, with the Phase 3 Final Rule at the federal level and the California Air Resource Board Advanced Clean Fleets rule at the state level.

Here's a recap of what the GHG3 and ACF rules entail:

Manufacturers, dealers, and fleets have also made significant investments over many years into electric trucks to meet emissions goals, and while doing so, have found EVs improve the driver experience and require less maintenance. The last Run on Less event held by North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE) centered around depot charging and showed incredible potential for fleets using vans and box trucks in regional applications, though charging even a few Class 8 trucks requires a herculean effort in terms of power generation and charging infrastructure. If it was difficult for the top fleets to operate a handful of electric trucks in California in 2023, what will it be like for rural small fleets in the Midwest in 2033?

But how fast adoption moves forward is up to the next POTUS, who is ultimately in charge of the EPA and other relevant enforcement agencies. Harris or Trump can tip the scales via who they appoint and how public policy is communicated.

“The Trump administration is likely not to put forth the same level of attention on enforcement around meeting those standards that you will have in a Harris administration,” offered Earl Adams Jr., partner in Hogan Lovells’ transportation regulatory group that helps large fleets and autonomous vehicle developers with regulatory compliance. “That's going to be the biggest distinction around emissions—the enforcement of the rules.”

That’s why, despite the listed timelines for when OEMs need to produce a certain percentage of zero-emission vehicles by a certain year, public opinion (in a democracy, not a dictatorship) is the true determining factor.

We can all speculate on which path is better, but it’s clear the candidates have made up their minds, so let’s revisit their positions.

Kamala Harris: Full speed ahead on EVs

Adams said Harris, a former Attorney General of California, will “lean forward” in ensuring that the government will meet the stated emissions goals.

Adams was chief counsel and then deputy administrator of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration during a large chunk of the Biden Administration, working closely with them on safety and driver initiatives. During his tenure, Congress passed both the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, which included billions of dollars to advance electrification to slow the advance of anthropogenic climate change.

“With Harris, we're going to see a likely continuation of getting the job done from all of the promises from the IIJA and the IRA,” Adams said. He added that “strong EPA standards, support of clean trucks, and California's efforts with zero emissions [are] going to continue in the Harris administration.”

As president of the Senate, Harris cast the deciding vote on the IRA, which provides billions in tax credits and incentives for EV end users and manufacturers. This includes:

- $1 billion for local, state, tribal, and school fleets to replace Classes 6 & 7 trucks and buses with EVs

- $3 billion for the U.S. Post Office for EVs and charging infrastructure

- $3 billion for clean ports

- $5 billion for manufacturing grants and loans

Another $25 billion is earmarked for EVs and clean transportation from the IIJA, a centerpiece of the Biden Administration’s first year. This had more bipartisan support, passing 69-30.

Under the $1 trillion infrastructure law, $7.5 billion was earmarked to build 500,000 public charging stations by 2030. The National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program comprises $5 billion and the Charging and Fueling Infrastructure (CFI) Discretionary Grant Program another $2.5 billion. The administration had received criticism for only eight charging stations built as of May 2024 under the program, with none before this year.

“In the last six months, there's been significant movement with federal highway getting money out in order to begin to build out those charging stations,” Adams noted.

In August, the U.S. Department of Transportation announced the number of EV chargers has doubled since Biden and Harris took office, saying 192,000 charging ports existed. One individual station can have more than one port.

The administration announced $521 million of that discretionary grant, or 20% of it, will allow the deployment of 9,200 charging ports in various rural, urban, and tribal lands.

Through the infrastructure law, the government plans to use $7.5 billion total to build out 500,000 stations as part of a national high-speed charging network. That equates to about $15,000 in funding per station. The average DC fast charger equipment and installation costs were over $100,000 in 2022, according to an ICF report.

Trump’s slow-and-steady business-friendly approach

“Trump, on the other hand, there's no incentive for him to [enforce the EPA and CARB rules],” Adams said. “These are not his rules. He wants fights with states like California in order to push back on their efforts.”

He’s not against EVs in general, though, with Tesla CEO Elon Musk as one of his staunchest supporters.

“Trump has softened his stance on EVs,” noted Pawan Joshi, sr. vice president of Product and Strategy at e2open, a supply chain platform provider. “In fact, he never was against EVs.”

Joshi said Trump’s preference was more free market, where the sector “lets each technology find its own space in the world.”

Trump is against the government compelling action and has said at virtually every opportunity available that he will repeal any EV mandates on his first day in office, preferring to let the private sector develop innovations organically. Federal mandates don’t technically exist, though it would be difficult to meet the 2032 standards without EVs.

Mandates do exist in California, though. Through CARB’s Advanced Clean Truck Rule, manufacturers may only sell zero-emission medium- and heavy-duty trucks in the state starting in 2036.

The NTEA – The Work Truck Association and the SEMA Association filed a lawsuit on Oct. 8 to impede the regulations out of concerns that zero-emission trucks will not be able to feasibly operate in vocational applications, leaving many of the state’s industries in a weaker state.

“Ultimately, work trucks must be available, capable, and affordable,” said NTEA president & CEO Steve Carey. “Left unchecked, the current suite of California regulations will severely curtail the ability of work truck users to obtain the vehicles they need to successfully and efficiently carry out their vital missions and support ongoing business operations in critical industries such as public works, utilities and telecommunications, emergency response, construction, food and agriculture, last-mile delivery and many others.”

Because the Supreme Court overruled the Chevron Doctrine this summer, the door is open for companies to challenge the EPA’s waivers that empower CARB to set mandates, Adams noted.

Trucking leaders’ POV

If fleets are forced to buy more expensive trucks and infrastructure, and spend money to retool their maintenance priorities from mechanical to electrical vehicles, those costs could lead to a new form of inflation.

Heavy-duty trucking will have to pay its own way into a cleaner future, with a Clean Freight Coalition study estimating a $1 trillion price tag to electrify the industry by 2040.

“We thought about how you can possibly calculate the end cost to the consumer, but that’s just impossible to do,” said Jim Mullen, executive director of the Clean Freight Coalition. “But I think we all know the cost of the tab is eventually going to be picked up in part by the consumer.”

Besides cost, fleets are concerned, as even at the high end of range performance, electric trucks are nowhere close to parity with diesel trucks.

A Ryder study released in May found it would take two electric trucks and two drivers to equal the productivity of one diesel truck. Light-duty/last-mile applications and to an extent, the medium segment, show far more promise in terms of ROI.

“Although we continue to be optimistic about the promise of electrification in medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, we continue to encounter challenges related to costs, vehicle range, durability, and charging infrastructure that complicate broader deployment of heavy-duty battery-electric trucks,” Taki Darakos, VP of vehicle maintenance and fleet service at Pitt Ohio, said to Congress last spring.

Small fleets and trucking companies, which comprise about 95% of the industry, are less equipped to handle EV mandates. In a The Washington Times op-ed written by Rep. Dan Newhouse (R-WA-04) and OOIDA President Todd Spencer, they explain:

With this regulation, the EPA is effectively mandating [electric trucks] while overlooking the significant hurdles that small-business truckers will face as they attempt to comply. First and foremost, current electric vehicle charging infrastructure is woefully inadequate. A notable shortage of charging stations, especially in rural areas, creates a bottleneck for long-haul truckers who need reliable access to power.

Spencer spoke to Fleet Maintenance this summer and said “the EPA has put the cart before the horse here,” citing the current range limitations electric trucks have, as well as their cost.

“They’re at least twice as expensive as [diesel trucks] currently are, and [diesel trucks] are not inexpensive now,” he said.

Hours of service and truck parking issues must also make charging trucks more complicated.

“[Longhaul drivers] struggle right now just trying to find someplace to get off the road that's safe for them to sleep,” Spencer said. “Now that would be the ideal time if you're going to have that electric vehicle charging, but we have nothing like that—and we're nowhere close to having something like that.

“Hopefully they'll get fantastically better over time, but we're not there yet,” he continued. “We think a mandate that says you have to have this by such and such day—and given all our previous experience we've had with EPA on their regulations is, we're not jumping up and down with glee over this nonsense.”

Because of the threat to small trucking firms, Newhouse is a co-sponsor of H.J. Res. 113, to disapprove the GHG3 rule, citing Congress’s authority under chapter 8 of title 5, United States Code. The resolution has 58 co-sponsors, all Republicans. A joint resolution needs two-thirds of the House and Senate, as well as the President, to sign off. Given Trump’s stance, it’s likely he would. Harris of course would not.

“[GHG3’s] just going to throw so many different complications into the industry,” Newhouse, who owns a 1,000-acre farm in Yakima Valley, told Fleet Maintenance in August. “I don't understand the logic behind it. We all want cleaner air…but we gotta’ have businesses that can survive.”

Newhouse is one of two remaining Republicans in Congress who voted to impeach Trump after the events of January 6, 2021 (and Trump has endorsed his opposition in the election, Jerrod Sessler). But they share common ground on questioning EV mandates.

Newhouse, seeking a sixth term, argued that once the larger fleets electrify, farmers will eventually, too, as they get larger fleets’ “hand-me-downs.” Even if federal grants are able to catalyze charging infrastructure buildout, the state may have serious issues supplying power to those chargers.

“There is a huge demand for electricity in our state,’ Newhouse said. “We can't produce enough electricity as it is—and with the increased demand from industries, like the artificial intelligence server farms that the big companies are building all the time in my area, there's just tremendous demand for electricity.”

He said Washington does get a lot of renewable power from hydroelectric dams, but “we're having to fight to save the dams.” For the last several years, environmentalists have sought to return Washington rivers to a free-flowing state to protect salmon migrations and tribal lands.

And turning to other forms of renewable energy is not without challenges.

“We don't want to cover up all of our farmland with solar panels or wind farms for that matter, either, so there's a struggle there,” Newhouse said.

Wind turbines would also have a detrimental impact on wildlife in the Pacific Northwest, particularly birds of prey such as the endangered golden eagle. In 2022, one renewable wind company, ESI Energy, was fined $8 million after 136 golden and bald eagles were killed after colliding with the company’s massive blades (dating back to 2012). Trump, by the way, relishes in pointing out how wind turbines kill birds.

To a much larger extent, a well-meaning push for EVs could have equally unintended consequences on trucking.

“A lot of members of Congress have good intentions, but just don't understand the real-world challenges that these businesses face, and what the result or the implications of some of the policies that they're advocating for would have on those industries and, in turn, on the American public,” Newhouse said.

He said rather than focus on EV technology that still needs time to improve and scale, or lowering the NOx on relatively clean diesel trucks, focusing on replacing the older trucks without emissions controls might be better.

“We should be putting our efforts in those areas that are going to make the most difference, right?” he said. “Looking at the older fleet, perhaps some incentives to change that out would give us a lot more bang for our buck.”

The representative is optimistic that the U.S. can find a balance between conserving the land and air and protecting small businesses.

“I'm very confident in the creativity of mankind,” he said. “I think people are very clever, and we can come up with ways to address and reach the goals that we want to achieve. [There’s] no doubt that over time, we'll get there.”

Finding a balance

According to E2Open’s Joshi, the one thing that is clear is that something must be done, because the transportation system in place needs to be improved to reduce the industry’s impact on the environment. The question is how far to go and how fast.

“At some point in time [moving to zero-emission vehicles] will need to happen, and we will need to make that trade off,” Joshi said. “And the question really here is, how do we actually prepare ourselves for it sooner or later, and how quickly do we move, or how do we slow down.”

And the president sometimes needs to tip the scales, Joshi said.

“When you're incubating something new, you need to put a finger on the scale for at least some period of time,” Joshi said, referring to incentives and grants. “And that's really what we’ve got to figure out: How much of that finger are you going to put on.”

He warned huge public projects such as President Eisenhower’s federal highway program need continued support, and the government can’t bounce between speeding up and slowing down. Otherwise, we’re just spinning our tire—lots of energy expended but no movement.

“What we did with our freeways back then… there was a sustained need, there was a drive, and it went through president after president, and we continue to invest in it,” he noted.

Successfully scaling EVs will likely require a similar strategy, but Joshi acknowledged not knowing who will lead the country has led to hesitancy.

“We don't know which way this is going to go, and that oftentimes leads to pumping the brakes—especially when you come close to a point where you think that the policy that was put in place might not be there or might be slowed down.”

He also noted the regulations ramping up through the next decade, which serve as a “carrot and stick,” aren’t perfect. And setting goals too high could be demotivating to those who otherwise might want to participate.

He related the EV question overall to the flywheel effect: “The biggest problem with the flywheel is getting it started.”

To create momentum, he advised collectively we “figure out those small, quick, logical wins, where you don't have to boil the ocean."

“That momentum actually helps you develop the appropriate technology, the appropriate manufacturing volumes that you need, the appropriate scales, and price points that you need,” he continued.

Ultimately, he said the biggest hurdle for the next administration is figuring out how to incentivize innovation in the heavy-duty segment without demotivating people with policies that hurt the industry.

“This [current GHG3] plan is maybe flawed at the onset, but at least it's a plan against which we can start recalibrating,” Joshi said. “And if we keep the politics aside, I think that's the way to get off our butts and make progress.”

Read more of our coverage on electric vehicles:

EPA finalizes GHG Phase 3 emissions rules

Analysis: The dark side of electrification

Can ZEV production, infrastructure scale in time for GHG3?

‘Destined to fail’: Trucking leaders, Congress question GHG3 final rule

Comparing HD EV mandates and rules with reality

ATAs' Spear gets 'aggressive' on election, emissions unions, and more in annual address

About the Author

John Hitch

Editor-in-chief, Fleet Maintenance

John Hitch is the award-winning editor-in-chief of Fleet Maintenance, where his mission is to provide maintenance leaders and technicians with the the latest information on tools, strategies, and best practices to keep their fleets' commercial vehicles moving.

He is based out of Cleveland, Ohio, and has worked in the B2B journalism space for more than a decade. Hitch was previously senior editor for FleetOwner and before that was technology editor for IndustryWeek and and managing editor of New Equipment Digest.

Hitch graduated from Kent State University and was editor of the student magazine The Burr in 2009.

The former sonar technician served honorably aboard the fast-attack submarine USS Oklahoma City (SSN-723), where he participated in counter-drug ops, an under-ice expedition, and other missions he's not allowed to talk about for several more decades.