The U.S. has a lot of potential for economic growth as the year winds down. “But we can’t get there because the supply chain is so clogged,” Don Ake, FTR Transportation Intelligence’s VP of commercial vehicles, said. “This is the worst supply chain crisis since World War II.”

While there is no food rationing in the U.S., like during WWII, commercial vehicle and trailer makers are rationing their offerings to fleets this year. Component supplies for commercial vehicles are stagnant and not improving this fall, according to FTR analysis. During FTR’s November update on the commercial vehicle market, Ake said the heavy-duty vehicle outlook has not improved since his October update, which pushed FTR to change its forecasts for 2022 and beyond.

Along with OEMs not getting enough deliveries, factories continue to face a labor shortage. On top of all this, backlogs at U.S. ports continue to slow the supply chain, forcing truck and trailer manufacturers to balance new orders against backlogged orders. “There is all this pent-up demand for commercial equipment—the problem is that it’s growing every month,” Ake said. “That pent-up demand is building and it is going to make it tough when things finally break loose to try to catch up.”

The sluggish supply chain forced FTR to “significantly” cut its Class 8 truck and trailer forecasts for 2022 from its previous outlooks: Down to 300,000 (from 335,000) new Class 8 truck builds next year and 315,000 new trailer builds (from 341,000) in 2022. Both of those new forecasts would still outpace OEM production in 2021. “They’re still good numbers, which means there’s going to have to be significant improvement a year from now—not a month from now, but a year from now,” Ake said. “They’re slightly optimistic forecasts, and they are subject to change if the supply chain issue just doesn’t get any better into the third quarter of next year.”

The 360,000 new Class 8 builds forecast for 2023 is achievable—if the supply chain improves—but Ake stressed, “that is a lot of trucks. We can do it, but we didn’t want to go any higher under these conditions because we don’t know if conditions will be at 100% in 2023. It’s so difficult right now to look out that far.”

Medium-duty builds could be even slower than Class 8. “We think it'll be a slower recovery next year for medium-duty because once the microchips start to flow, the gains first go to the automotive sector, then the gains will be in the Class 8 sector, and then the medium-duty will get their increases later,” Ake explained.

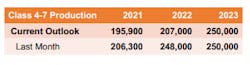

This led FTR to slash its 2022 Classes 4-7 production outlook from 248,000 to 207,000. Ake said that FTR expects fewer than 200,000 new medium-duty vehicles to be built in 2021. “In this case, we might not catch up to demand until 2024.”

The underlying pressure on the commercial vehicle market “continues to mount,” according to Eric Starks, FTR’s chairman and CEO. “We keep pulling our forecasts back. That’s such a weird thing to see because that underlying pressure is there to say, ‘You need to be moving your forecast higher’—and we keep moving it down. It is only because of the supply chain constraints.”

The commercial vehicle industry isn’t unique to these problems, Starks noted. “All industries are having these problems that Don talked about: This issue that we’re seeing with a World War II-type of environment is pervasive throughout—and that’s where this gets really tricky in trying to nail that down.”

Supply chain clogs

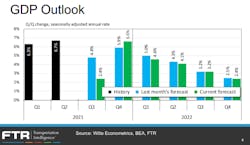

Ake pointed to the currently clogged supply chain as a significant obstacle for the transportation and industrial sectors that could stymie economic growth well into 2022. FTR has already readjusted its GDP outlook for Q3, which ended on Sept. 30.

In October, FTR expected a 4.8% growth in GDP for Q3; it now expects half that growth once all the indicators are tabulated. After a weaker Q3, “we’re not showing a lot of catch-up” between now and the start of 2023, Ake said. As of November, FTR is forecasting 6.6% GDP growth in Q4, followed by slower growth through each quarter of 2023.

“It looks like we’re running behind and, based on what I said about that clogged supply chain, it’s going to be tough to hit that Q4 (2021) number,” Ake explained. “Things are going to have to open up a little bit and things are going to have to improve some in the general economy to get there.”

The “goods transport” GDP growth was sluggish in Q3 this year, Ake noted. It grew just 0.3% compared to the overall 2.4% GDP growth across the U.S. economy. The slow supply chain is putting a lot more drag on transportation and industrial growth than it is on the service sector, Ake noted. While, as of the start of November, FTR was forecasting a 9.1% growth in goods transport, Ake said “that’s going to be a stretch forecast. Things are going to have to improve a little bit to hit that. It’s a doable number—but just knowing what is going on in the economy, it’s going to be tough to hit.”

With the GDP forecast falling for the end of this year, so is the truck freight outlook, Ake said. “The good news is the freight growth is still good. Even looking through 2022, you’ve got growth close to 4%—after we get past the first quarter. So there’s going to be solid freight growth in 2022.”

Ake expects that growth in 2022 to continue to propel the commercial vehicle equipment markets. “The bottom line is that even though the GDP forecast was downgraded a little bit, freight does not seem to be hurt that much.”

Port delays

“Things are not moving in the supply chain. Therefore things are not moving in the OEM build rates,” Ake said. “We've got a huge backlog. And nowhere is that backup more pronounced than at the ports.”

In September, there were more than 40 ships backed up at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, the largest ports in the U.S. “We thought that was very bad,” Ake noted. “But now, there are 100 ships waiting at ports as of Oct. 19. So we went from 40, which we thought was bad, last month to 100, and then to make it worse, there were 45 more ships on the way that they expected to arrive later that week.”

While wait at the ports grows, the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are charging carriers $100 per day for each container not unloaded past its designated due date. This, Ake said, is the government and ports’ way of trying to slow the number of ships showing up. “That strategy has its faults because if you’ve got a containership loaded in China and people have ordered that merchandise, they want that merchandise as soon as possible,” he explained. That means you’re going to have to come over to the port and get in line. So what we have is a big mess. And it doesn’t look like it’s going to get resolved soon.”

Microchips

OEMs’ lead time to get microcontroller chips, the semiconductors used in trucks, is getting worse. “It actually lengthened in October,” Ake said. “So, at a minimum, things did not improve for our industry concerning semiconductors.”

Steel and aluminum supplies, however, are improving. Ake noted that steel prices fell 8% and aluminum was down 11% from peak prices in September. “It’s better—but it’s not good,” he said.

Like the vehicle supply chain, the trailer supply chain is still sluggish, Ake said. “We watch that because it’s similar to the truck supply chain—but not impacted by semiconductors,” he explained. “But at least 25 different components subjected to late deliveries.”

CV orders and builds

Class 8 vehicle orders have remained stagnant since April. “That’s because the OEMs are managing their orders and their backlog very carefully in this uncertain supply chain and labor environment,” Ake explained.

Ake said that OEMs are “basically looking at their current production rate and only booking” what they can produce. Other than a surge of nearly 40,000 Class 8 orders—driven by a few large fleets—in August, orders have stayed between 23,000 and 28,000 since the spring.

Class 8 production has followed a similar pattern, Ake noted. New heavy truck builds bounced between 22,000 and 25,000 since April—except a dip down to 15,100 in July, one of the poorest months for semiconductor deliveries this year.

The builds and orders are mirroring each other, which is rare in the industry “because it’s difficult to look too far into the future,” Ake said.

He said that trailer makers, who have “a big backlog” are managing their orders and production differently from truckmakers. “The trailer OEMs are basically trying to move orders around, move the backlog around, s that they can build at a certain level,” Ake explained. “So they haven’t been taking in a lot of orders.”

Other than a spike in September—like the August Class 8 order surge—driven by a few large fleets, trailer orders had not topped 16,000 since March. Trailer production has stuck between 22,000 and fewer than 25,000 since March.

“The OEMs are building all they can—it’s not an OEM capacity issue—it’s a supplier issue,” Ake said. “We’re stuck in a pattern and we’re not breaking out of that pattern anytime soon.”

This article originally appeared on FleetOwner.com.